Minimizing the Relational and Developmental Costs of AI

There’s some serious AI fatigue going around with the constant development of new tools. If you’re not careful, this feeling can devolve into a view of complete AI rejectionism. So, I figured I would write this post today to help myself and others deal with the increasingly challenging dilemma of when you should and should not use AI.

First, a parable from Tiger Woods. In a series of “Tiger Talks” from Golf Digest, Tiger recalls his father’s advice when determining how hard you should swing the golf club. He said, “swing as hard as you can as long as you can hit the ball with the center of the face.”

What was revealed to me after reflecting on this was that we don’t need a binary response to AI, but constraint. Not “swing hard or don’t,” but “swing hard so long as X.”

It reminds me of a book written by Sam Harris in 2010 titled, “The Moral Landscape.” In it, Sam advocates for a way of determining human values based on the effect of well-being. His argument is a topic for another time, but what’s helpful is the landscape analogy itself and its usefulness in ethical decision-making.

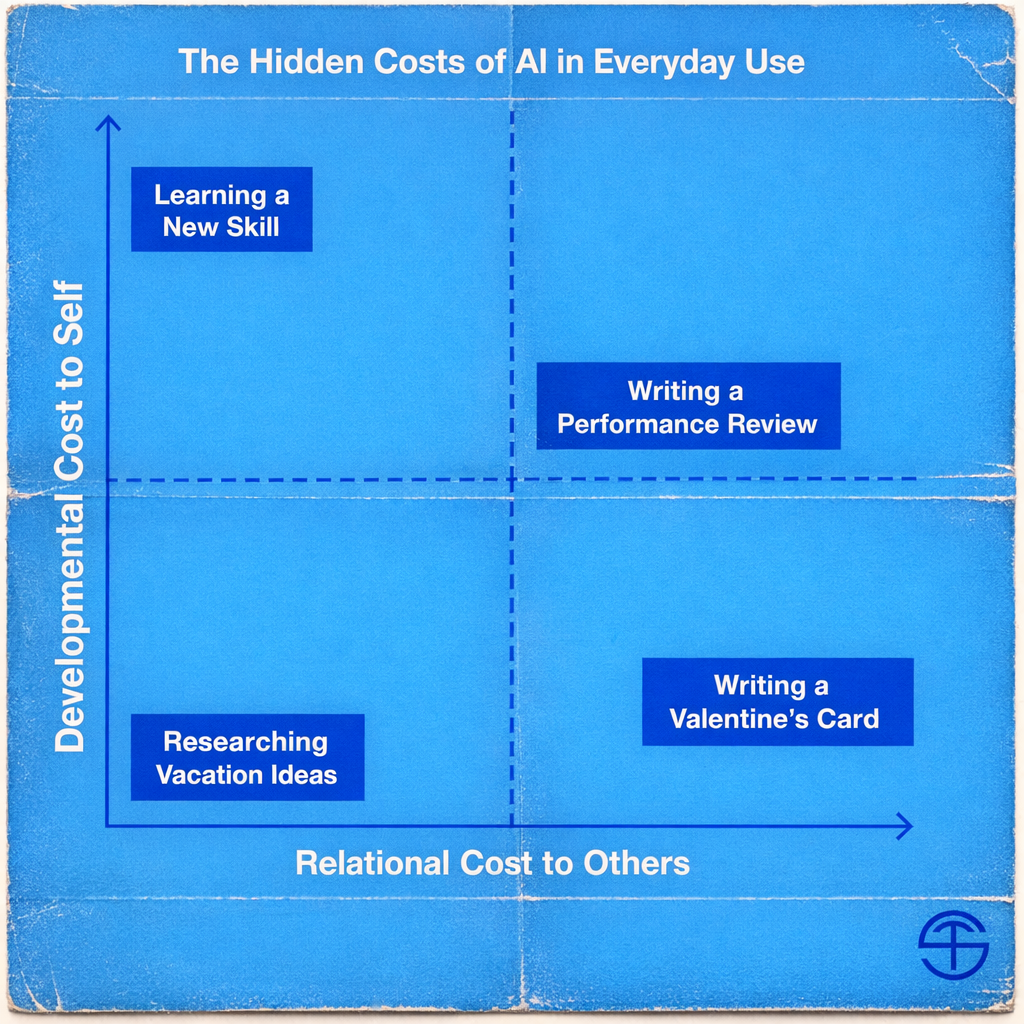

After thinking through this a lot lately, I’d like to propose a couple of constraints that really get to the crux of the issue. In principle, my suggestion is to use AI as much as you want to accomplish your goals so long as you minimize the following:

Relational cost to others

Developmental cost to self

On the opposite side of the same coin, we can say this also means to maximize care and effort. I believe the fruits they bear are worth it.

So, in creating our decision matrix, I realize we must first have a foundational agreement of why these things are important, or else we risk hollow aesthetics.

A whole essay could be written alone on the importance of these values, but I’ll summarize them as follows: If we care about the sustainability of the human race, it is absolutely vital that we maintain 1) our ability to build sustainable relationships with actual humans and, 2) at least a moderate level of independence from machines.

If you agree, we can start to establish constraints for AI usage based on our “landscape” of values, then start to plot out common scenarios that give us a clearer understanding of the axes. Let’s review a few examples.

First, let’s look at high relational cost and low developmental cost. Imagine you have AI write a Valentine’s card to your spouse. It could probably do a good job, but it would come at a high relational cost. Your spouse has a predetermined standard of genuine care and effort that makes the card or gift valued. The friction involved in creating something genuine creates the value, not the gift itself. While writing Valentine’s letters may not need to be a repeatable skill that needs developing, the relational cost is high.

Of course, it’s not black and white. There are things you can do to still use AI while minimizing the cost. You could chat with AI to get feedback on your thoughts, structure them in a logical way, or ask for feedback. As opposed to pasting a full AI template, producing your own work that involves an AI-assisted thought process certainly moves the action back down the axis.

Next, let’s look at moderate relational and developmental costs, such as drafting a report to your boss or writing landing page copy. As opposed to communicating with your spouse, the emphasis on personal connection and standard for authenticity is less. However, there is still an expectation from your boss or audience that your ideas are your own, accurate, and helpful. AI can help systematically organize your thoughts, research and analyze, and even draft outlines. However, the more you use it to copy and paste, the more you increase your costs.

Venturing into muddier waters, let’s consider something like using AI to write a performance review for someone who works under you. The relational cost is potentially high in terms of outsourcing your judgment to AI, while the developmental costs also carry some risk of becoming unable to clarify standards, values, and what good work looks like without the help of a machine.

While AI can help you check tone and blind spots, opting for a fully templated performance review nullifies the reflective process. Bottom line, would you be uncomfortable telling this employee how much AI wrote their review? It’s an additional litmus test with broad application.

Finally, we can discuss high developmental costs and low relational costs, such as learning a new skill. With any form of education, a significant portion of the actual learning process is doing the work, facing challenges, and internalizing all of the context that comes with it. Asking AI to code you an app may be a new skill that becomes quickly accessible, but unless you’ve become knowledgeable on how code is actually deployed and maintained, you’re operating blindfolded.

It’s not that we need to develop every skill, but if we do not exercise our judgment and capabilities, we risk atrophy.

As Ryan Holiday recently said, “As AI becomes better at sounding smart, we’ve got to get better at actually being smart.”

These few examples are obviously not comprehensive of the possible plots along our axis, as the landscape can have infinite placements. However, we now have a guide and guardrails on how to reasonably think about our decisions around AI usage.

In a time where there is so much confusion and FOMO on new AI tools, we need more mental models like this to give us a tangible framework for creating and benefiting from production that keeps our standards in place.

In the future, I believe we will need some mechanism of transparency that shows what was produced with AI and to what extent. Why? Because care and effort still matter.

I used AI to help stress test this framework, but wrote it myself. Not because AI couldn't express the point in a similar or better way (it probably could), but because I care enough about the reader and the creative friction involved to limit the costs of doing so.